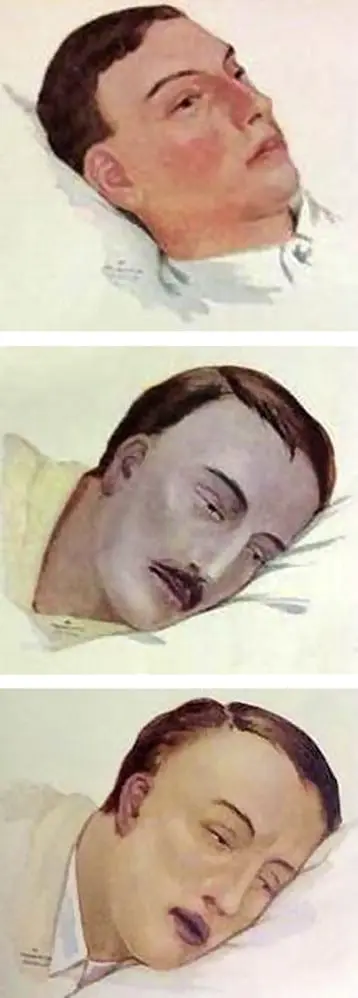

Symptoms of the Spanish flu, the name given to the 1918 flu pandemic, differed from seasonal flu symptoms in surprising ways. While the onset brought about familiar fever, body aches, and a sore throat, the illness progressed quickly to bleeding from the nose or ears and petechial hemorrhages, bleeding under the skin that looked like a spreading red rash. Victims coughed up blood stained mucus. Hands and faces turned blue with inadequate oxygenation of the blood and death soon arrived.

The men start with what appears to be an attack of la grippe or influenza, and when brought to the hospital they very rapidly develop the most vicious type of pneumonia that has ever been seen. Two hours after admission they have the mahogany spots over the cheek bones, and a few hours later you can begin to see the cyanosis extending from their ears and spreading all over the face, until it is hard to distinguish the coloured men from the white. It is only a matter of a few hours then until death comes, and it is simply a struggle for air until they suffocate. It is horrible. One can stand to see one, two or twenty men die, but to see these poor devils dropping like flies sort of gets on your nerves. We have been averaging about 100 deaths per day, and still keeping it up. There is no doubt in my mind that there is a new mixed infection here, but what I don’t know.”

~ letter from Dr. Roy Grist, Camp Devens, Massachusetts, 29 September 1918

Though many deaths were attributed to bacterial pneumonia, a secondary infection caused by influenza, researchers now believe a cytokine storm was the likely major cause of mortality. In layman’s terms, a cytokine storm is a hyperactive immune system response which results in lung inflammation and fluid buildup that leads to respiratory distress. Victims of the 1918 flu pandemic basically drowned when their own body fluids filled their lungs.

Another consequence of the cytokine storm was that it killed mostly young adults, people in their 20s and 30s who are usually at less risk from viral infections, when their healthy immune systems over-reacted. In 1918, during the last year of World War I, it was the servicemen—not only spreading the virus from place to place on crowded trains and troop ships—but the ones who died. More soldiers died from the Spanish flu than were killed in battle during the war.

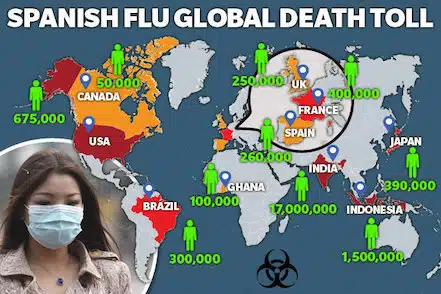

Today, the Spanish flu death toll is estimated at 50 to 100 million people worldwide. It is thought to have infected one-third of the world, and its case fatality rate is estimated to be at least 2.5%, so for every 100 cases, on average 2.5 people died. Some 675,000 Americans died. Exact numbers are unknown due to a lack of medical record-keeping and censorship that was occurring because of World War I.

I first became interested in the 1918 flu pandemic during the 2009 swine flu outbreak. Then, we found 200,000 deaths alarming; I wanted to understand the devastation of 50 million dead. Learning scientists believe the pandemic originated in my home state of Kansas and reading about the unusual Spanish flu symptoms further hooked me and the idea for my novel began to spread.

Leave a Reply