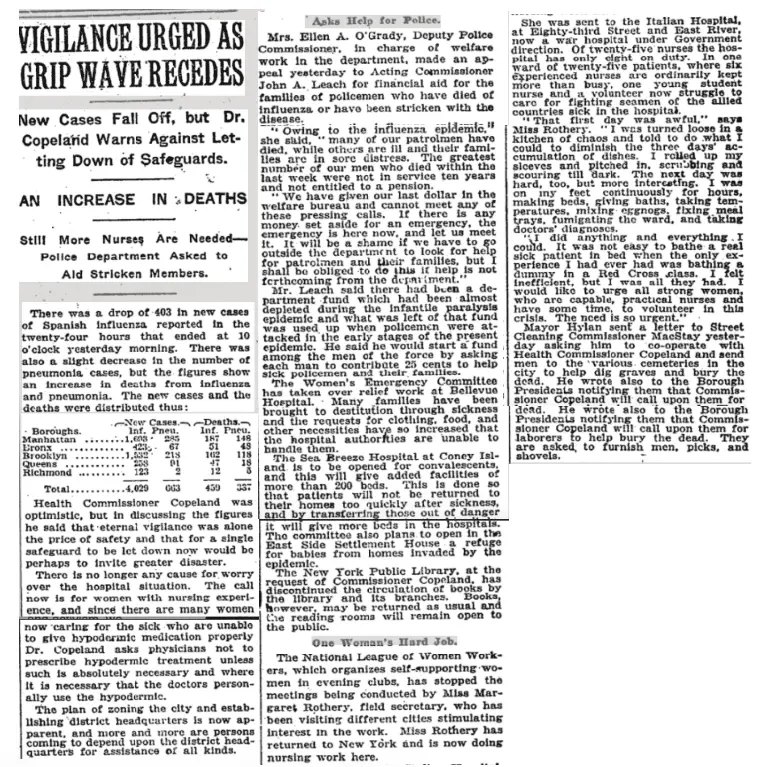

This headline from the New York Times could be talking about new cases of COVID-19 falling off, but it refers to the 1918 Spanish influenza. Then, too, New York was trying to find the fine line between optimism and pragmatism.

“Health Commissioner Copeland was optimistic, but in discussing the figures he said that eternal vigilance was alone the price of safety and that for a single safeguard to be let down now would be perhaps to invite greater disaster.”

Current New York Governor Andrew Cuomo said on April 12, 2020, a devastating 758 lives were lost from COVID-19 the previous day, each with a face, a name, and a family. It marked the sixth straight day with over 700 deaths from the coronavirus. On a more hopeful note, Cuomo reported the number of people being hospitalized continued to decline, and the amount of people being discharged from the hospital was on the rise, indicating a plateau.

“The Women’s Emergency Committee has taken over relief work at Bellevue Hospital. Many families have been brought to destitution through sickness and the requests for clothing, food, and other necessities have so increased that the hospital authorities are unable to handle them.”

Today, as well, as we hope for a decrease in cases, our communities find themselves struggling to provide our essential workers and most vulnerable populations with support. Finding ways to protect and aid those most at risk to hunger, poverty, disease and homelessness is essential in addressing inequity during our recovery.

“Owing to the influenza epidemic many of our patrolmen have died, while others are ill and their families are in sore distress. The greatest number of our men who died within the last week were not in service ten years and not entitled to a pension.”

The concern during the 1918 Spanish influenza about the police force who had no benefits, reminded me of a present day essential workforce who rarely have benefits: our truck drivers. My brother is a truck driver, transporting oil so that natural gas compressors function and people can cook and stay warm. He reminded me recently he doesn’t have the luxury to quarantine at home. He’s right. It is a luxury to be able to shelter at home. As we determine how to best respond to all of the impacts of COVID-19, we need to remember those with the least access to economic, social and political resources and power who are most likely to contract and die from the disease and are also most likely to lose their income or health care during shutdowns and social distancing measures.

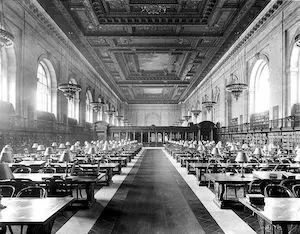

“The New York Public Library, at the request of Commission Copeland, has discontinued the circulation of books by the library and its branches. Books, however, may be returned as usual and the reading rooms will remain open to the public.”

Keeping the public library open in 1918 is different from today as we now know respiratory droplets transmitted between people is the major way infections spread. The concern during the influenza of 1918 was due to the belief that dust from contaminated books could spread infectious diseases. Though we aren’t able to visit beautiful library reading rooms today, it did remind me of the power of books in these distressing times, and I hope my own historical novel comforts and offers hope during dark days.

“Mayor Hylan sent a letter to Street Cleaning Commissioner MacStay yesterday asking him to co-operate with Health Commissioner Copeland and send men to the various cemeteries in the city to help dig graves and bury the dead.”

Sadly, this too is a similarity among the two pandemics. As morgues fill in New York City, some victims of COVID-19 will join some from the 1918 Spanish influenza and be buried in the potter’s field on Hart Island, where the city has buried its poor or unclaimed dead since the mid-1800s.

I’ve been researching and writing my novel about the 1918 Spanish influenza for almost ten years—many days so immersed in a pandemic that life now in the time of COVID-19 is eerily similar, and I find myself confused about what year it is.

Leave a Reply